The Imaginary: A Story to Believe

by Maria Elena Gutierrez

Studio Ponoc’s beautiful animated feature “The Imaginary” introduces us to Rudger (Kokoro Terada/Louie Rudge-Buchanan), the imaginary friend – or “Imaginary” – of young Amanda (Rio Suzuki/Evie Kiszel). When their bond of friendship is severed, Rudger discovers deep truths about the twin worlds of reality and imagination, and the doorways that connect the two. Directed by Yoshiyuki Momose, key animator of Studio Ghibli’s classic “Spirited Away,” the film is adapted from the novel written by A.F. Harrold and illustrated by Emily Gravett.

From the opening frames, “The Imaginary” invites us to explore the unrestrained space of imagination. We follow Rudger and Amanda as they plunge through a world filled with shifting landscapes and populated by fantastical creatures. When their adventure finally comes to an end, we realize the whole journey has taken place inside Amanda’s attic bedroom, a dream-odyssey fueled by the creative vision she shares with her imaginary friend.

As the narrative unfolds, it becomes clear that Amanda is only able to access this fantasy world because she is a child. In this way, “The Imaginary” earns its place in the rich tradition of storytelling that explores the natural ability of children to access the space of imagination … an ability they sadly lose when they grow up.

We sense this loss in Amanda’s mother, Lizzie (Sakura Andô/Hayley Atwell), who cannot see Rudger and is unaware of the adventures her daughter has with him. Yet, as her own mother reminds her, Lizzie once had her own imaginary friend – a dog called Fridge. Nor has Lizzie abandoned the magic completely. She owns a bookstore and, in the world of “The Imaginary,” literature is a key that unlocks the door between humdrum reality and the magical realm of imagination.

Early in the film, Amanda expresses her fear that one day she will grow up and forget all about Rudger. Her fear is partly driven by unresolved grief over her father’s death, and further accentuated by the appearance of a terrifying man called Mr. Bunting (Issei Ogata). Together these things introduce an undercurrent of dark threat that counterpoints the multicolored whimsy of Amanda’s imaginary world.

In a fateful encounter, Amanda flees Mr Bunting only to be struck by a passing car. As she lies in the hospital in a coma, Rudger starts to disappear. By this point, as an audience, we care deeply about Rudger’s fate and empathize with his dawning horror at his looming fate. A profound existential question has suddenly become all too real: “What happens to an Imaginary when their real-world companion dies?”

The answer becomes clear when Rudger meets a mysterious cat with one red eye and one blue eye. Is it a coincidence these are the same colors as the pills Morpheus offers to Neo in “The Matrix?” This feline familiar escorts Rudger through a magical doorway to a beautiful Italianate city known as the Town of Imaginaries. Here live all the imaginary friends who have been abandoned by their former companions. In the town library, the feisty Emily (Riisa Naka/Sky Katz) introduces Rudger to a motley crew of Imaginaries including a pink hippo called Snowflake and a skeletal entity called Cruncher of Bones.

Rudger also encounters Imaginaries who were once friends of such artistic luminaries as Picasso, Beethoven and Shakespeare. Describing the role of Imaginaries, Emily says, “We make humans and their world more beautiful.” Imaginaries also function as Muses, it seems, and artists become great because they retain the ability to think like a child.

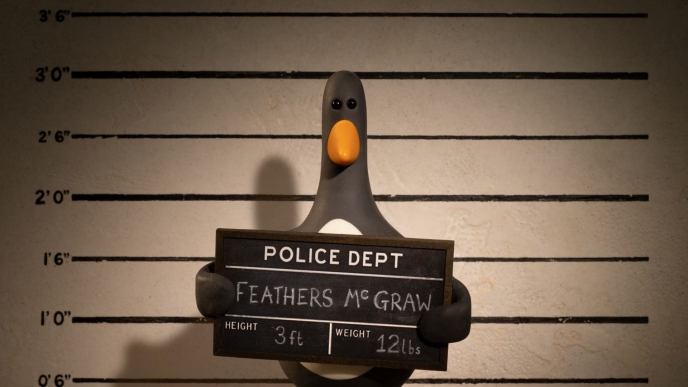

Rudger goes on to learn that all Imaginaries live in fear of Mr. Bunting. Accompanied by his own Imaginary, a spooky ghost-girl with cavernous eyes, Mr. Bunting wants to eat all the Imaginaries he can get his hands on. Superficially a represenation of death, this monstrous figure in fact sheds a sickly light on our relationship with our own imaginations.

As an adult who has not forgotten his own imaginary friend, Mr. Bunting seeks not to experience imagination but to index it. While he clearly savors the taste of every Imaginary he eats, the act of consumption is essentially one of appropriation. He is not a creator, but a chronicler … and a hideous one at that.

The pain brought by Mr. Bunting connects directly to the sadness lying at the heart of “The Imaginary.” We learn that Rudger was born out of the tears Amanda shed following the untimely death of her father. While Mr. Bunting wants to destroy all grief by consuming it, Rudger’s tragic origin story reminds us that grief is something we must carry with us. Death is a given, something to be accepted and even celebrated. Grief cannot simply be boxed up and tucked away.

With its constant switches between the twin worlds of imagination and reality, this is a story tailor-made for the medium of animation. Animated by hand and gorgeously rendered in a beautiful visual display, the adventures of Amanda and Rudger carry us away on a stream of consciousness roller coaster. A furry snow giant strides through a twinkling Christmas village. Space aliens are repelled in spectacular fashion by a giant bubble gun. Paper birds fly on delicate origami wings. Buoyed by a tremendous score by Agehasprings and Kenji Tamai, which also features motifs by classical composers including Handel, “The Imaginary” is a soaring celebration of beauty, art and creativity.

At the climax of the film, Rudger confronts Mr. Bunting in the hospital room where Amanda lies unconscious. Dream and reality blur as the world of imagination collides with our own, in a tour de force of dazzling animated action. Finally remembering her own childhood, Lizzie calls out to her old friend, Fridge the dog, who returns from exile in the Town of Imagination to save the day. Thus the film shows us there is hope for us all, if only we can see through the eyes of a child.

Fridge’s appearance reminds us of what the old dog said to Rudger earlier in the film, when they first met in the Town of Imagination: “Never mind truth. All that matters is the story you believe.” This is precisely what “The Imaginary” invites us to do – believe. Nowhere is this invitation more heartfelt than in the film’s final frames. Echoing the words he spoke in the opening scene, Rudger closes the circle with the following rhapsody: “A bird not ever seen. A flower not ever seen. A breeze not ever seen. A night not ever seen. Have you ever seen anything so wonderful? I have.”

Dr. Maria Elena Gutierrez is the CEO and executive director of VIEW Conference, Italy’s premiere annual digital media conference. She holds a Ph.D. from Stanford University and a BA from the University of California Santa Cruz. VIEW Conference is committed to bringing a diversity of voices to the forefront in animation, visual effects, and games. For more information about the VIEW Conference, visit the official website: http://viewconference

Subscribe to the VIEW Conference YouTube channel:

https://youtube.com/c/

Facebook: https://facebook.

YouTube: https://youtube.com/

Twitter: @viewconference

Instagram: view_conference

VIEW Conference newsletter: Sign up here

#viewconference2025

#savethedate 12-17 October 2025